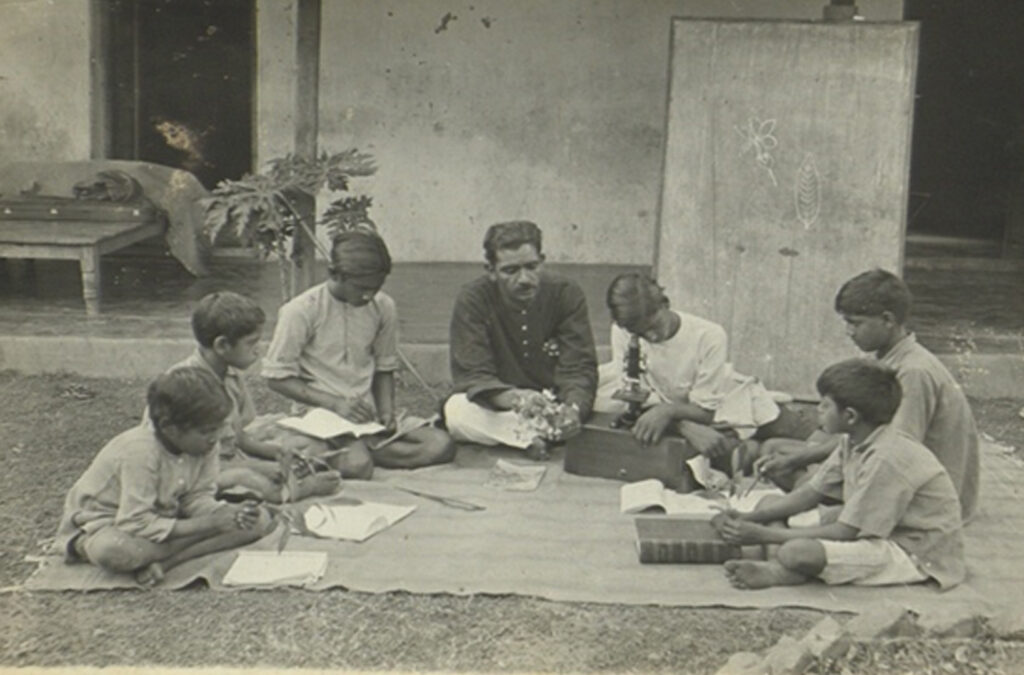

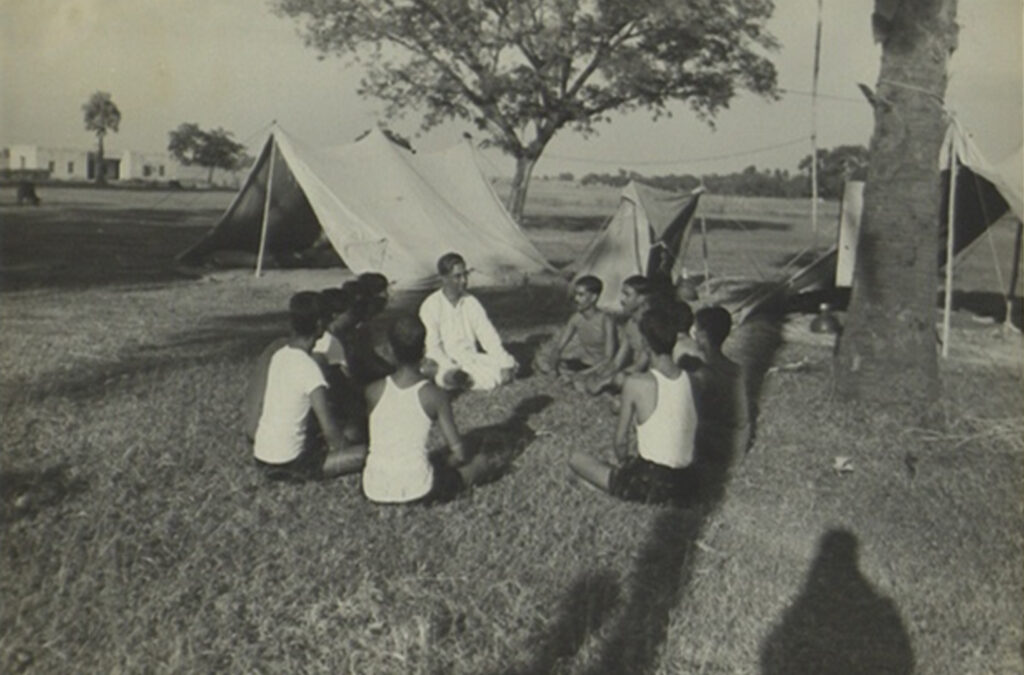

The poet Rabindranath Tagore was the founder of an institution that we know today as Visva-Bharati University in the twin campuses of Santiniketan and Sriniketan in rural southern Bengal about a hundred miles north west of Calcutta. Starting it as an experimental school in 1901 he added an international university in 1921 and an institute of rural reconstruction in 1922. This institute of rural reconstruction was named Sriniketan. It was a pioneering experiment in bringing economic and social reform to the villages surrounding his Santiniketan school which had gone into great decline mostly due to the infestation of malaria in the area, the indifference of our urban society to the problems of the village and the apathy of the villagers to stir themselves both mentally and physically.

Rabindranath wrote, ‘Among the politicians of those times, there was not one who regarded the rural people as members of our country. I said to a prominent leader of the Indian National Congress at the Pabna conference that the state can progress only if we pay attention to our lowly people, if we make an effort to transform their lives.’(1)

In 1889–90, Rabindranath was sent by his father to take charge of the Tagore family’s agricultural estates in East Bengal. The estates were owned by Rabindranath’s grandfather, Dwarkanath Tagore (1794–1846). These were six sprawling agricultural estates that spread out between Orissa and East Bengal. The estates in Orissa were in the Cuttack district. Those in East Bengal were at Sahajadpur in Pabna district, Kaligram in Rajsahi district, and Birahimpur in Nadia district. As the head of the Tagore family Maharshi Debendranath presided over these properties.

A time came when Debendranath asked his youngest son, Rabindranath, to leave Calcutta and move to the Birahimpur estates’ headquarters at Selidaha on the banks of the mighty river, Padma, which was looked upon as the Ganga of East Bengal. The family houseboat called the Padma Boat was stationed at Selidaha and anchored at Selidaha’s high banks. Writing from Selidaha in 1889, Rabindranath described the sandbanks that surrounded the houseboat as follows:

‘Our house-boat is moored to a sandbank on the farther side of the river. A vast expanse of sand stretches away out of sight on every side, with here and there a streak, as of water, running across, though sometimes what gleams like water is only sand. Not a village, not a human being, not a tree, not a blade of grass—the only breaks in the monotonous whiteness are gaping cracks which in places shows the layer of moist black clay underneath. Looking towards the East, there is endless blue above, endless white beneath. Sky empty, earth empty too—the emptiness below hard and barren, the overhead above arched and ethereal. One could hardly find anywhere such a picture of stark desolation.

But on turning to the West, there is water, the currentless bend of the river, fringed with its high bank, up to which spreads the village groves with cottages peeping through—all like an enchanting dream in the evening light. I say ‘evening light’ because in the evening we wander out, and so that aspect is impressed on my mind. How extraordinary and beautiful our world really is: something easy to forget in Calcutta. When the sun sets each evening behind the peaceful trees along this small river, high above the boundless expanse of sand thousands and thousands of stars suddenly appear— you have to see it to happen to grasp its wonder.’(2)

Though stationed at the zamindari headquarters, Selidaha, Rabindranath travelled frequently to the other estates by the Padma Boat. He lived for days and nights on the boat. This was the first time in his life that he was seeing the countryside and coming into contact with the tenant farmers of the entire estate. He gave a personal and intimate account of what led him to start the work of rural reconstruction. That was why the address was published with the title ‘Sriniketan er Itihas o Adorsho’ (The History and Ideals of Sriniketan). In that speech, he spoke of the shame he felt over his way of life as follows: (3)

‘The needs of my work took me on long distances from village to village, from Selidaha to Patisar, by rivers, large and small, and across ‘beels’ and in this way, I saw all the sides of village life. I was filled with eagerness to understand the villagers’ daily routine and the varied pageant of their lives. I, the town-bred, had been received into the lap of rural loveliness and I began joyfully to satisfy my curiosity. Gradually, the sorrow and poverty of the villagers became clear to me, and I began to grow restless to do something about it. It seemed to me a very shameful thing that I should spend my days as a landlord, concerned only with money-making and engrossed with my own profit and loss. From that time forward, I continually endeavoured to find out how the villagers’ minds could be aroused, so that they could themselves accept the responsibility for their own lives. If we merely offer them help from outside, it would be harmful to them. The critical question was to ask how they could be stirred to life. I was haunted by that thought and decided to act on it. Children living in hunger, and young women married as child brides and helplessly chained to their marriages felt to Rabindranath like a mockery of what human life should be. His tenants were mostly lower caste Hindus and poor Muslims. Their everyday life was dismal and full of despair.’ (4)

Echoes of the pain of their everyday life perturbed Rabindranath deeply. He expressed those personal feelings vividly in series of letters to his niece, Indira Devi Chaudhurani (1873–1960, author, daughter of Rabindranath’s second brother, Satyendranath Tagore). The letters were later compiled into a volume and published in 1912 with the title Chhinnopotro (Torn Letters). In one of them, he wrote of a very deep ‘inner’ stirring, as follows: ‘On that morning in the village the facts of my life suddenly appeared to me in a luminous unity of truth. All things that had seemed like vagrant waves were revealed to my mind in relation to a boundless sea. I felt sure that some Being who comprehended me and my world was seeking his best expression in all my experiences, uniting them into an ever widening individuality which is a spiritual work of art. To this Being I was responsible; for the creation is His as well as mine … I felt that I had found my religion at last, the Religion of Man, in which the infinite became defined in humanity and came close to me so as to need my love and cooperation.’(5) It was this deeply felt compassion for the common man that turned him into a man of action, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. That was how the Selidaha experience became so important to his self development, and the consequences led to the making of the Sriniketan Institute of Rural Reconstruction by which he worked with the villages surrounding his Santiniketan school.

NOTES

1.‘City and Village’, address delivered on seventh anniversary of the Sriniketan Institute, 6 February 1928, in Towards Universal Man (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, Reprint, 1967), p. 304. [Hereafter, Towards Universal Man]. 2. Glimpses of Bengal: Selected Letters by Rabindranath Tagore, (London: Papermac edition, 1991), pp. 25–26. Translation by Krishna Dutta and Andrew Robinson.

3. ‘Sriniketan er Itihas o Adorsho’, address to the workers of the Institute of Rural Reconstruction, Sriniketan, on Rabindranath’s last visit there in 1939, in Palli Prakriti (Calcutta: Visva-Bharati Publishing Department, 1962), pp. 96–104. English translation by Marjorie Sykes titled ‘The History and Ideals of Sriniketan’, in The Modern Review, November 1941, Volume 70, Number 5,

p. 5.

4. L.K. Elmhirst, ‘The Foundation of Sriniketan’, in Rabindranath Tagore Pioneer in Education, Essays and Exchanges between Rabindranath Tagore and L.K. Elmhirst (Calcutta and London: Visva-Bharati Publishing Department and John Murray, 1961) p.20.

5. The Religion of Man (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1931), pp. 94–96.

Image courtesy : Rabindra Bhavan Archive, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan

Jibansmriti archive Blog

Joint editor : Arindam Saha Sardar Curator & president, Jibansmriti Archive

Biyas Ghosh secretary, Jibansmriti Archive.

Chief assistant editor : Moumita Pal

Editorial board members : Pramiti Roy, Ankush Das & Sujata Saha.

Vol. 1, No. 5, 10 August 2025